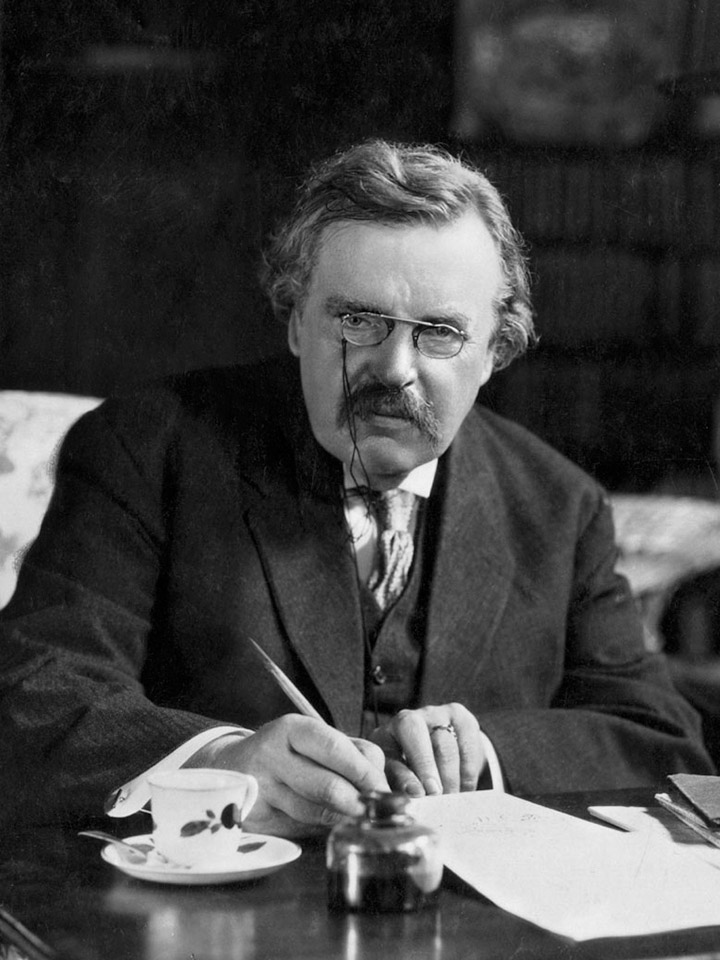

G. K. Chesterton

Birth Name: Gilbert Keith Chesterton

Nickname: G. K. Chesterton KC*SG, Prince of Paradox

Born: May 29, 1874 in Kensington, London, England

Died: June 14, 1936 in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England

Time Period: Modern

Expertise: Art Critic, Debater, Essayist, Journalist, Lay Theologian, Literary Critic, Novelist, Orator, Philosopher, Playwright, Poet

Known For: A Defence of Skeletons, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study, Father Brown, Irish Impressions, The Everlasting Man, The Man Who Was Thursday, The Napoleon of Notting Hill

Quotes

Interesting quotes by G. K. Chesterton

“Music with dinner is an insult both to the cook and the violinist.”

“People generally quarrel because they cannot argue.”

“A good novel tells us the truth about its hero; but a bad novel tells us the truth about its author.”

“Lying in bed would be an altogether perfect and supreme experience if only one had a colored pencil long enough to draw on the ceiling.”

“I regard golf as an expensive way of playing marbles.”

“The way to love anything is to realize that it may be lost.”

“A yawn is a silent shout.”

“Coincidences are spiritual puns.”

“There are no uninteresting things, only uninterested people.”

“Poets have been mysteriously silent on the subject of cheese.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Bio

A brief biography of G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born May 29, 1874 in Kensington, London, England. Better known as G. K. Chesterton, or jovially referred to as “Prince of Paradox”, he was an illustrious writer of poetry, stories, essays, and articles. He is best known for his novel, The Napoleon of Notting Hill.

Coming from a family of Unitarians who practiced sporadically, G. K. was fascinated by the occult. As a young boy, he and his brother, Cecil, would dabble with Ouija boards. Chesterton was educated at St. Paul’s School in London, a Clarendon school established in 1509. He later attended Slade School of Art, with a desire to become an artist—specifically an illustrator. G. K. also took literature classes but would never graduate from college. However, the lack of a college degree would not prevent him from becoming a prolific writer—between writing close to eighty books and the copious amounts of articles and essays he wrote for his newspaper columns, his output was astounding.

Chesterton’s dear friend, Hilaire Belloc, a poet and essayist himself, put them in close association. Being partners for the publication, G. K.’s Weekly, established in 1925, it was originally founded in 1911 by Belloc under the title, The New Witness, but kept the new name up until a few years after Chesterton’s death. The book, The Outline of Sanity, contains excerpts of Chesterton’s journalistic work from their publication. Another friend of G. K.’s was George Bernard Shaw—an Irish playwright. Often they would take part in friendly debates about indifferences, which Chesterton enjoyed thoroughly. However, it was George Bernard Shaw who would bestow Chesterton and Belloc with the name, “Chesterbelloc,” in regard to their teamwork and friendship. It is said that Chesterton and Shaw once acted as cowboys in a silent film, but unfortunately, it was never released.

G. K. Chesterton’s literary career began at several publishing houses starting in 1895—the first being Redway in London. Then in 1896, Chesterton would take a job at the T. Fisher Unwin publishing house, where he was employed for about six years. During his time at Unwin, he would further his career in journalism as a literary and art critic. Following his depature from T. Fisher Unwin, Chesterton would be a regular columnist for Daily News. Also in 1905, he would have another recurring column in The Illustrated London News.

Prior to this, in 1904, Chesterton published his influential novel, The Napoleon of Notting Hill. The year after, he began writing for said publications, and penned Charles Dickens: A Critical Study, earning him more recognition and acclaim in the literary world.

G. K. Chesterton was a passionate fellow. He advocated against Britain’s Mental Deficiency Act of 1913. He wrote an entire book on the subject, titled, Eugenics and Other Evils, and though he started the manuscript around 1910, it wasn’t completed and published until 1922. The ideas behind eugenics thorougly appalled him and he wrote, “It is not only openly said, it is eagerly urged that the aim of the measure is to prevent any person whom these propagandists do not happen to think intelligent from having any wife or children. Every tramp who is sulk, every labourer who is shy, every rustic who is eccentric, can quite easily be brought under such conditions as were designed for homicidal maniacs. That is the situation; and that is the point... we are already under the Eugenist State; and nothing remains to us but rebellion.”

In 1929, Chesterton would contribute to the fourteenth edition of Encyclopedia Britannica—an article about Charles Dickens and part of a section on humor. Following all his beloved accomplishments, BBC Radio would request for him to do a sequence of radio shows. Chesterton agreed. He enjoyed the talks he delivered, esepcially since he was permitted to improvise. Having his wife nearby—along with the freedom to speak his mind—it enabled a more personable and visceral quality that Chesterton could share with the audience. It is said that G. K. Chesterton delivered at least 40 talks per year with the BBC. After Chesterton died, and becasue of his popularity, a BBC official recounted, “...in another year or so, he would have become the dominating voice from Broadcasting House.”

G. K. Chesterton’s work has been influential to other writers down to the present day. In The Napoleon of Notting Hill—which was set in the future, yet retained the current politcal structure of Chesterton’s day—he depicted the state of democracy in Englang in 1984, where kings were randomly chosen to lead the country. It is believed by some that this inspired George Orwell’s naming of his own famous work, Nineteen Eighty-Four, or perhaps was simply an homage—since before becoming critically acclaimed, a young Eric Arthur Blair (using the pseudonym, George Orwell) had his first essay published in Chesterton’s publication, G. K.’s Weekly. Another author heavily influenced by G. K. Chesterton is Neil Gaiman. Gaiman dedicated his co-authored book, Good Omens, “To the memory of G.K. Chesterton: A man who knew what was going on.” Neil Gaiman also modeled a comic book character after G. K., indiscretely naming him “Gilbert”—portayed as a stout, friendly man, who had a love for paradoxes—in The Sandman. The Napoleon of Notting Hill was also greatly appreciated by Michael Collins, a revolutionary Irishman. G. K. was also a prodigious contributor to periodicals, such as The Illustrated London News, Daily News and his own publication.

Before Chesterton’s death, Pope Pius XI would install him as “Knight Commander with Star of the Papal of St. Gregory the Great” (KC*SG).

Gilbert Keith Chesterton died on June 14, 1936 in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England. The cause was congestive heart failure. The last words he spoke were to his wife, Frances Blogg, in the form of a greeting. The funeral mass was carried out in the Westminster Cathedral in London on June 27, 1936. The sermon was served by Ronald Knox, who said, “All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton’s influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton.” G. K. Chesterton is buried in Beaconsfield in the Roman Catholic Cemetery.

ADVERTISEMENT

Works by G. K. Chesterton

Download free G. K. Chesterton books. Listen to G. K. Chesterton audiobooks.

ADVERTISEMENT

External Links for G. K. Chesterton

G. K. Chesterton on Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G._K._ChestertonG. K. Chesterton on Wikisource

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Author:Gilbert_Keith_ChestertonADVERTISEMENT

Other Authors

See other authors of the Modern period

- James Bernard Fagan

- Ernest Hemingway

- Samuel Jackson Holmes

- H. P. Lovecraft

- Wilfred Owen

- Leo Szilard

- Nikola Tesla